Love, Marriage & Hearing Loss....How do you cope?

By Kemi Mobuse - Thursday, July 14, 2016

John and Julie Olson have been married for 46 years, and

throughout that time they have worked to maintain their strength as a couple.

They decided early on that they would not be limited by Julie’s progressive,

bilateral hearing loss. “We were not going to allow ‘hard of hearing’ to

destroy our personal and social life,” says John.

Hearing loss can cause feelings of isolation for one or both

partners, but the Olsons have actively avoided that. “Early in our marriage…we

sat down and talked about the fact that I am social and so is Julie,” says

John. “We both agreed we would make it work. We win; hearing loss loses.”

|

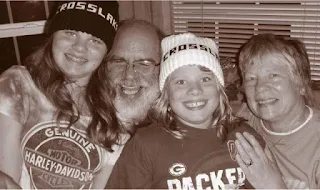

| John and Julie Olson with their granddaughters, Colleen and Kelly. |

Karen Sinclair, 55 (pictured at the top with her late

husband, Rick), acknowledges that hearing loss can cause frustration and create

resentment in both partners, and that letting negativity build can lead to

significant problems. “You have to learn patience,” says Sinclair, a paralegal

from Kanata, Ontario.

Karen’s husband, Rick, who passed away in 2010, had

bilateral hearing loss. His hearing was reduced to less than five percent in

each ear before he received a cochlear implant.

Working to prevent frustration—and communicating openly when

it did occur—helped both the Sinclairs and the Olsons maintain lasting, loving

relationships. They used basic steps, which any couple can employ, to build and

maintain strong marital relationships.

Set Expectations; Educate Your Partner

When the Olsons came to understand the logistics of Julie’s

hearing, the couple took a big step forward in their communication. “A

hard-of-hearing person may take up to five seconds to process the answer to a

simple yes or no question,” says Julie Olson, 70. She points to the fact that

frequently, a hard-of-hearing person only catches a percentage of the words

spoken, and has to extrapolate the rest of the meaning. “That’s like light

years to a hearing person, who is expecting an answer within a millisecond.

They start saying things like ‘Never mind, it wasn’t important,’ which to us is

a message that ‘we are not important.’ That may not be the intent, but that is

what is mentally ingested.”

Instead of allowing this to happen, the couple made sure

that John knew what to expect in their communication. “Once we both accepted

the reality that there is a cognitive delay in offering a response to a simple

question, it helped,” says Olson.

Partners should make sure each one understands the other’s

capabilities. Karen Sinclair says that

Rick, the partner with hearing loss,

didn’t understand how much his wife could hear. “He thought that hearing people

could hear everything,” she remembers. For example, when he was in the living

room, Rick didn’t know that when she was running water in the kitchen sink, she

couldn’t hear him. He called to her, but got no answer. He called again; no

answer. Ironically, says Karen, “he would get frustrated because I couldn’t

hear him.” Talking about this issue helped both partners understand each

other’s perspective a little better.

Make a Plan

Planning ahead and discussing contingencies is an important

part of setting expectations. With hearing loss, otherwise “normal” situations

can escalate to emergencies, and emergency situations can be terrifying.

Recalling her late husband’s hearing loss, Karen Sinclair

describes an innocuous situation that could have been very unpleasant. “We had

this dog. He was a bit of a character,” she says. “I’d gone to take the garbage

out, and he was barking and jumping and carrying on at the door, and he somehow

managed to drop the latch.” Locked out, Karen realized that Rick couldn’t hear

her banging on the door or ringing the bell. Fortunately, they had exchanged

house keys with a neighbor, and she was able to get in.

Karen had other concerns, too. “I would worry about the

smoke detector,” she says. “It could go off and he wouldn’t hear it.” And when

Rick came home one day to find Karen unconscious, he was panicked. Fortunately,

their son was home and could call 911 for Rick; it turned out Karen had had a

seizure. The incident highlighted for the couple the need to anticipate how

hearing loss can alter or prevent communication in an emergency.

Communicate About Communicating

Make sure your partner understands how you feel. Michael

Smith, 55, who’d already been gradually suffering hearing loss in his right

ear, lost all hearing in his left ear 17 years into his marriage with Mary. He

felt incredibly frustrated by his family’s treatment of his hearing loss. “The

way my family dealt with my hearing loss was to ignore it,” says the father of

five, who used to post information on the refrigerator about how his family

could best communicate with him—to no avail. Smith wound up becoming isolated

in social situations, even around the dinner table with his own children.

Smith went to counseling to deal with his feelings of

resentment and its resulting depression, but the root problem — that of feeling

isolated from his family — was never really solved. Instead, technology has

given him back some hearing and he’s been able to return to social situations.

“I could again become an active member of the family, and I am having to become

more assertive to let people know that it’s not OK to continue to ignore me

like [they did] when I was severely hard of hearing,” says Smith.

Being ignored is incredibly painful. Over the 46 years of

their marriage, John Olson has shared his wife’s pain when conversations have

left her in the dark. “The most difficult thing about this relationship is

watching people talk around your hearing-impaired spouse,” says Olson. “You

both know how much it hurts.”

Karen Sinclair understands completely. She says that her

late husband, Rick, who was profoundly deaf for about 10 years prior to getting

a CI, was relatively accepting of the inevitable moment when conversations

would march on without him. While Rick was sanguine about it, however, Karen

would “see red” when people were rude to her husband because of his hearing

loss.

Communicating effectively with each other is the first step

in resolving some of these issues.

Educating others is the next. John Olson

says that the couple is clear with new acquaintances that Julie is hearing

impaired. “Openness is paramount to getting support from others,” agrees Julie,

who is now an advocate for the hard of hearing. “When we choose to hide our

hearing loss, people think we don’t care about them. And, most people think

that hearing aids will bring back perfect hearing. We have to explain to them:

That’s not reality.”

Take Joy

All relationships have bumps in the road, but the partners

who can work through these issues together—and take something positive from

them—are the most successful. “Yes, I get frustrated, and we may bark at each

other, but we usually end up laughing about it,” says Julie Olson.

Karen Sinclair remembers some of the little things about

Rick’s hearing loss that made her laugh. One time, shortly after he’d gotten

his cochlear implant, Rick called her via TTY at work and

growled, “Don’t they ever stop?”

“What?” Karen asked, surprised and a little worried.

“The birds!” Rick replied. “I can’t stand it!”

0 comments